Lead Out: Water systems nationwide miss crucial deadline to identify their lead pipes

Many water systems in the country missed their first lead inventory deadline to identify pipes in need of replacement.

Washington, D.C. (InvestigateTV) — On a sunny October day, two volunteers wearing neon-colored vests traveled door to door in a Southeast Washington, D.C. neighborhood. In their arms were iPads and pamphlets. They canvassed and spoke to homeowners who listened.

Their message wasn’t part of a political campaign. Instead, these two volunteers canvassed on behalf of DC Water, a utility company that serves approximately 700,000 residents in the District of Columbia, as well as provides wastewater treatment services to parts of Maryland and Northern Virginia.

InvestigateTV tagged along with DC Water to get an exclusive look as crews walked around, and excavated roads. The goal: to inform customers about their lead replacement program. It’s part of an effort to meet a federal mandate to all water departments to identify and replace lead pipes.

“Just this past year, we have knocked on over 24,000 doors to educate them about our lead-free DC program,” said Kirsten Williams, DC Water’s chief communications officer.

Williams describes DC Water’s lead removal program as an efficient and proactive effort to ensure the safety of the water lines serving local homeowners.

One such homeowner, Samantha Lasky, took advantage of the program by reaching out to DC Water for a test to determine whether the century-old pipes beneath her home contained lead.

“It’s incredible that there’s a pipe out there that’s 130 years old and carrying water to us every day,” Lasky said.

DC Water conducted what’s called a “test pit” outside of Lasky’s home, which is a small excavation dug into the ground to determine the pipe material. If the service line is found to be lead, crews replace it.

As crews conducted the test pit outside of Lasky’s home, they discovered that it was not lead underneath the surface, it was copper.

“In this incident, we have some copper, which we were not expecting, which is why we come out and do a test pit- because in old neighborhoods, like Washington DC, you don’t always know what your service line materials are,” Williams said.

DC Water also discovered that the city had more lead lines than they originally estimated.

“When we started this program in 2019, we thought we had about 28,000 lead service lines. When we came out to do those test pits and try to better identify what that service line material is, we realized we had a much higher number. So, we’re about 42,000, but even that, there are some unknowns with that,” Willams said.

Across the country, water departments face significant challenges in identifying the number and location of lead service lines. Some have found previously unknown water lines and inaccurate historical data to help them locate these pipes.

In many cases, these systems have revealed more lead pipes than departments initially expected. The unknowns in their databases only add to the complexity of an already murky picture of lead pipe distribution.

A key milestone in the 10-year plan to eliminate lead from drinking water came in fall 2024, when water systems nationwide were required to submit their initial inventory of lead service lines by an October 16th deadline

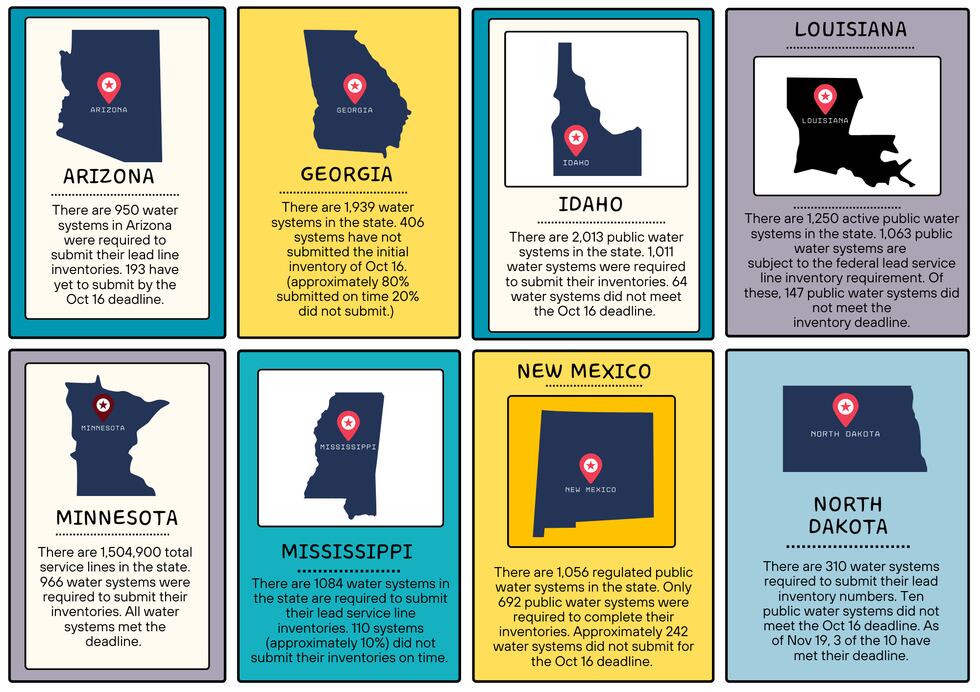

InvestigateTV sent public record requests to states’ environmental departments asking for their lead inventory numbers to further understand the complexity and hardship water departments face in replacing lead pipes.

Our investigation found that some states, like Massachusetts, reported that their water system submitted 99% of their inventories.

However, InvestigateTV found some states where water departments missed that deadline and did not turn in an inventory.

For example, in Georgia, more than 400 of the 1,900 water systems in the state did not meet the October 16th deadline. In Virginia, about 20% of the approximately 1,500 water systems also did not turn in their inventories for that October deadline too.

But this deadline is nothing new.

In April, InvestigateTV reported that even though the inventory deadline was soon approaching, states were warning that there could be setbacks. Attorneys general in 15 said were pushing back on the lead and copper rule, calling it an “unworkable, underfunded and unnecessary, under ‘an impossible’ timeline.”

The History of Lead Marketing and Promotion in America

For more than a century, the United States has struggled with the dual challenges of lead pipes and public health risks.

Richard Rabin, a public health researcher, has spent more than 30 years of his life documenting the history of the lead industry.

He believes there is a direct link between health issues and lead pipes.

“We have a legacy of, a history of an industry that promoted its product, ignored the public health warnings, and now we’re paying the price,” Rabin said.

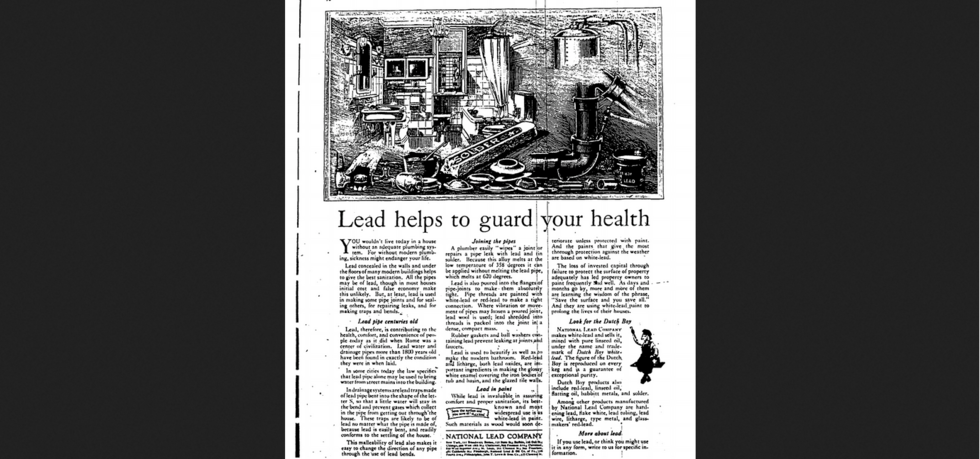

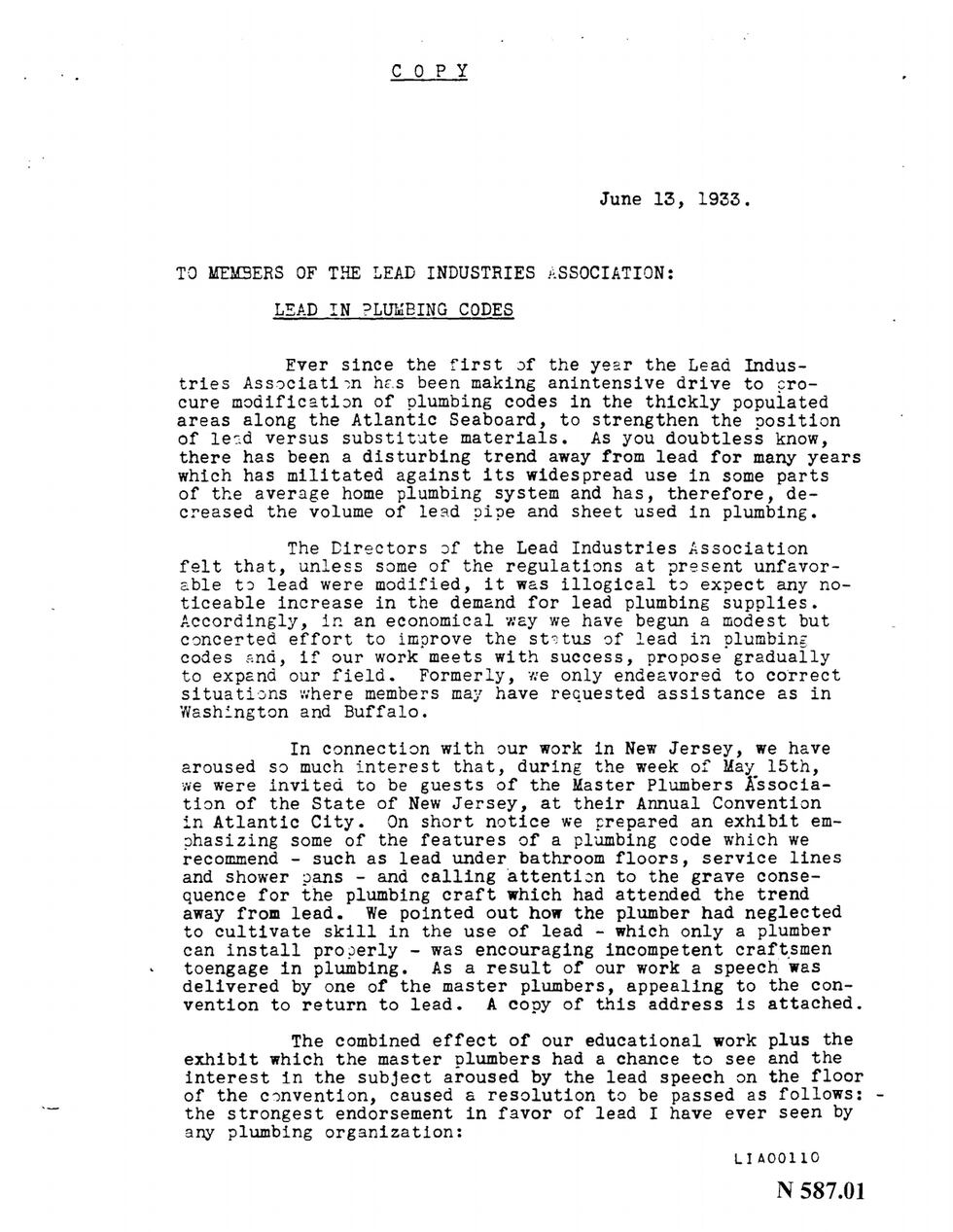

While sifting through a large box of lead industry records Rabin has kept for decades, he showed InvestigateTV messages from companies dating back a century, downplaying the dangers of lead pipes.

For example, one article Rabin retrieved stated that “lead helps to guard your health.”

He found that the Lead Industries Association (LIA), the prominent lead trade association at the time sent workers around the country to promote the use of lead, using ads in newspapers and magazines.

Rabin said public health officials knew by the early 1900s that lead was a potential health hazard, but lead industry leaders continued to promote the use of lead pipes.

“I became extremely upset that they were selling their product at the expense of the health of children and adults,” Rabin said.

The LIA filed for bankruptcy in 2002, but the lingering effects and efforts of that area are still felt today, as crews continue to dig for answers buried beneath homes and streets across America.

Newark, a model city for lead pipe replacements

As cities and towns work to identify and replace lead pipes, Newark, New Jersey is viewed by the federal government as a national model. In just three years, the city successfully removed the majority of its lead service lines.

Kim Gaddy, founder and director of the South Ward Environmental Alliance, played a pivotal role in this effort by fostering a stronger relationship between city officials and the community, welding that relationship even tighter.

“When you hear stories about our great city of Newark, it’s always the negative stories, the homicides. But to know that we were a leader, and we replaced 18,000 plus lead service lines in a community of individuals that was marginalized. This can be done when everybody comes together,” Gaddy said.

Gaddy is a Newark native and calls it home. She’s also the founder of the Alliance, an environmental justice organization serving more than 80,000 people in the community. For Gaddy, Newark’s success goes beyond financial investment, it’s also about the air they breathe and the water they drink.

Addressing the challenges in her community meant tackling the issue of lead pipes head-on. Lead exposure became a deeply personal concern for her when she discovered that her Godson had suffered from lead poisoning at just six years old.

“That was my first real exposure to lead poisoning. And it was from paint chips. But I also began to say, well, what about the water?” Gaddy said.

It didn’t take long for the nation to turn its attention to Newark after city officials discovered elevated levels of lead in homes and schools – levels that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency wouldn’t allow today.

In 2017, Newark faced a crisis when three consecutive tests revealed that the city’s water had exceeded the federal limit of 15 parts per billion for lead. In June 2017, the City of Newark said testing revealed 22% of 129 samples of the City’s water exceeded the federal limit for lead. Since more than 10% of samples exceeded the federal threshold, the City had to inform its residents. As of May 2020, every six-month test since June 2017 has shown exceedances. The source of the problem was traced to a failed corrosion control treatment at one of the city’s water plants, which served about half of Newark.

As the city worked to address the issue, Gaddy’s expertise as an environmental and community activist proved invaluable.

“No level, no level at all of lead in drinking water is acceptable. And so we began to just have this whole campaign, but in partnership with the city. It wasn’t that, you know, we were going to rubber stamp everything they said, but we truly believed that the community needed another messenger and person to tell the story,” Gaddy said.

For her, rebuilding community trust in state and local government was the first barrier to addressing the crisis and removing the lead.

“When you think about community, oftentimes they are the ones who don’t have a seat at the table. And so, when we decided to engage those individuals firsthand, it gave them the opportunity to really be in the room and to let their voices be heard so that now they could be a part of the solution,” Gaddy said.

She, along with other activists, clergy , and city leaders, launched an effort to educate the community about the dangers of lead pipes and inform them about the removal process.

“The narrative was flipped. So, it wasn’t so much I’m being told that my water is okay. No, I’m being able to have a seat at the table, read what’s happening, understand what’s happening, and then make the right kind of choices that I need to make for my family,” Gaddy said.

In just three years, the city of Newark removed more than 18,000 lead service lines, setting a powerful example for other cities to follow.

It’s a challenge that many states, cities and towns now face – but one that Gaddy believes is achievable, as long as the will of the city and its people remains strong.

“Commit to it. Involve the community, trust the community, and do right by the community, and you could get it done,” Gaddy said.

Newark’s strong reputation for lead service line replacement was somewhat tarnished in October when both the city and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection discovered that a third-party contractor hired to replace a small percentage of lead lines may not have fully complied with all the required standards.

Two individuals were arrested and charged with fraud for failing to complete the replacement of lead service lines.

Despite the indictment, the city maintains confidence in the success of its lead service line replacement program, which has resulted in over 23,000 replacements and remains a national model for reducing lead exposure risk.

“It was about 28 that was found, that we replaced under this particular contractor during this audit. We dug up a little over 400. And they were replaced immediately, which is about 1% of the total program,” said Kareem Adeem, director of Newark Water & Sewer.

Futuristic Solutions to a Century-old Problem

Despite the numerous challenges surrounding lead service line replacements, there may be a futuristic solution to the century-old problem of faulty record-keeping.

To address the shortcomings of the past, BlueConduit, a water analytics company based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, is leveraging modern technology to help locate lead pipes and discover the unknowns.

Eric Schwartz, co-founder of BlueConduit, explained that the company uses predictive modeling analytics to identify where to dig for lead service lines in Flint, providing valuable insights to local decision-makers and accelerating the removal process.

Flint garnered national attention in 2014 after corroded pipes poisoned city residents.

“We started using data science machine learning to predict address by address where the lead was,” Schwartz said.

Schwartz believes that machine learning, or AI, is the key to helping communities tackle their lead inventory challenges. Blue Conduit is currently working with more than 350 cities, towns, and communities across the country to help complete their lead service line inventories.

The technology also helps reduce labor and costs for water departments while pinpointing areas with higher concentrations of lead to help make the process easier.

“When we look at other service lines, where we know all of those pieces of information, except the material, we can then make a prediction of best guess…what’s the likelihood that this address has a lead pipe,” Schwartz said.

Washington, D.C., is also leveraging the same cutting-edge technology and community engagement to remove lead from its water systems.

“For us, it eliminates the ability to not have to test pit every home to identity. There’s a cost to test pitting, and certainly for us, we want to make sure we’re maximizing every dollar on replacing lead,” said DC Water’s Williams.

She knows that utilizing every available resource to remove lead from one of the nation’s oldest cities is crucial to ensuring cleaner water lines for homeowners, children, communities, and doing so by one block at a time.

“We have seen throughout the country that lead in our water has led to really terrible consequences for people in communities around the country. So I’m glad that here in DC, we’re already taking care of it,” Lasky said.

The next step in the process is for all states to submit their complete inventories to the EPA by March 31, 2025.

Copyright 2024 Gray Media Group, Inc. All rights reserved.